Unravelling Knitwear in Fashion

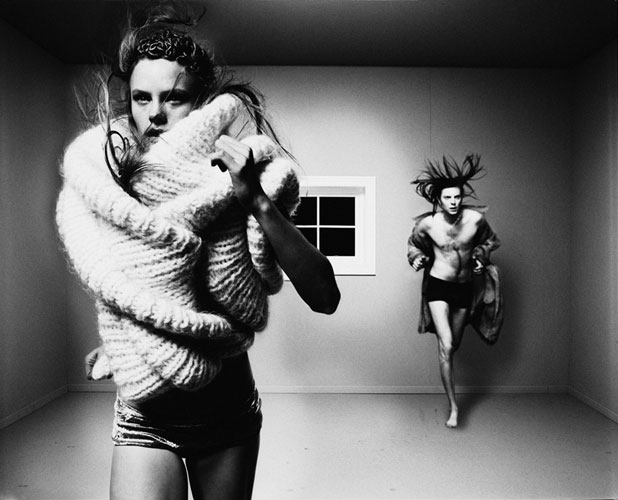

/Sandra Backlund, Collection ‘Body, skin and hair’ (c) Photography: Johan Renck, Stylist Ellen Af Geijerstam

by Sarah Scaturro

I first met Karen Van Godtsenhoven when I was in Brussels last fall giving a lecture as the keynote speaker at the Camouflage Takes Center Stage conference at the Royal Military Museum. She gave a wonderful presentation on camouflage in Belgian fashion - it was quite hilarious to watch all of the stiff military personnel (mostly men) chuckle uncomfortably as she showed a video of Bernard Willhelm's Spring/Summer 2004 presentation parodying the US military's "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" policy in which partially-clothed men walked out of a closet (literally) wearing camouflage and face paint and then proceeded to irreverently jump on a couch (see the video at the bottom of this post).

Van Godtsenhoven is a relatively new fashion curator with a promising future - "Unravel," the exhibition on view now at Momu, is the first time she has taken the helm as lead curator (along with the guest curator Emmanuelle Dirix, a lecturer at Central Saint Martins and Antwerp Fashion Academy.) Following is an interview in which she talks about why she chose to dissect knitwear in fashion, what some of the challenges were in mounting an exhibition on this topic, and who she thinks some of the best knitwear designers are today. Her upcoming projects include exhibitions about Nudie Cohn and Walter Van Beirendock.

Fashion Projects: What inspired you to curate a show about knitwear in fashion?

Van Godtsenhoven: It's been a favorite subject and fascination of ours here for years. It was literally a research file ‘in the cupboard’ waiting to come out. With the current vogue for knitwear with young designers, but also the popularity of knitting within the wider public (think knitting cafés, ravelry.com, guerrilla knitting), we thought it was the right time for the subject to come out of the closet.

Unravel Installation, MoMu, Antwerp, Photo: Frederik Vercruysse

You selected a mix of historical and contemporary pieces - besides the actual structure of the garments (non-woven, single element) did you find any surprising similarities or differences in how knitwear was used in the past as compared with today?

Yes, the changing status of knitwear in fashion is a subject of endless study possibilities. Whereas we see knitwear emerging very early on as a kind of handmade utility garment (related with warmth, hygiene and sturdiness - this element is still with us today), machine knitting is also a very old technique (16th century, long before the industrial revolution), which was very technologically advanced and resulted in very fine gauze- like materials. There are a few dresses and jackets in the show from the 17th, 18th and 19th century, of which many visitors cannot believe that they are knitted, the same goes for many of the 19th century socks: they are embellished and knitted so finely it looks like embroidery or lace. So, before the industrial revolution, machine knitting was considered high-class. Now we see an opposite appreciation: handmade goods are more costly than machine made ones.

There are many continuing ideas about knitwear (jersey is still used for sportswear, handmade goods are still associated with the domestic sphere and now also the DIY movement), but the short history of knitwear in fashion shows that there have been many (r)evolutions: from underwear and swimwear to Chanel’s jersey dresses and marine sweaters, to Schiaparelli and Patou’s abstract motifs, to the knitted A line dresses in the sixties, as a result of the sexual revolution, and the deconstructed 1990s knitwear that had its origins in the 1970s punk movement. Knitwear has always gone with the waves of society, and that makes it very interesting. I think the so called ‘revival’ (whilst knitwear has never really been away from the catwalk) of knitwear these days can be linked to heightened ecological awareness and a longing for handmade and body-hugging goods, and I'm curious in which form it will come back in the future.

Bathing suit by Elsa Schiaparelli, ca. 1928 (c) Condé Nast Archive/CORBIS

Were there any challenges to exhibiting knitwear pieces, especially due to conservation issues?

Yes, both the heavy and voluminous pieces, as well as the fine gauze-like knits weigh themselves down under their own weight: knitwear is a more ‘open’ material than a woven cloth and will hence open up even more when hanging. This is a risk for skirts and dresses stretching, or growing longer up to 40 cm in the 5 months they are on show.

We covered the busts and mannequins with a fine jersey, which ‘clings’ well to the knitted silhouettes and keeps the pieces in place - we also provided waist and hip supports for the dresses. The very frail pieces are displayed flat in cases. Knitwear is really always best kept flat...I've learned this from my own experience!

Tilda Swinton for Sandra Backlund. Published in Another Magazine, Autumn 2009 (c) Photography by Craig McDean, Styling by Panos Yiapanis

What are your favorite objects in the exhibition? Were there any objects you wanted but couldn't obtain?

I have to say that my favorites change often, but amongst the returning are: the four sweaters by Elsa Schiaparelli, the 3D silhouette by Sandra Backlund (made out of four different experimental dresses), and the knitted metal sweater by Ann Demeulemeester - it may sound like a punk outfit but it’s actually more like a very delicate jewel when you see it.

Oh, and maybe also the knitted boliersuit and miniskirt by Courrèges!

We were very sorry not to be able to get the sweater with holes (1982) by Comme des Garçons as it went missing, since it’s such a seminal piece for knitwear in high fashion - it completely changed our view on the formless in fashion, and regarding knitwear, to the ‘un-knitted’. In the title group ‘Unravel’ you see the evolution of how ‘waste’ (punk sweaters with holes, knitted in glaring colors) became fashion (Comme des Garçons, and many Belgian designers like Martin Margiela and Ann Demeulemeester, Raf Simons) and is now hugely popular (Mark fast, Rodarte).

You included new avant-guarde designers like Sandra Backlund and Mark Fast. Who are some other emerging knitwear designers that we should keep an eye out for?

Good question, there are so many! I like Sandra Backlund and Mark Fast because of the very personal and highly different ways they treat knitwear. I also think Craig Lawrence, Kevin Kramp (menswear), Christian Wijnants (Belgian) and Iben Höj (from Denmark) all have very interesting, personal styles. Some come up with highly structured, sculptural pieces in raw wool, others treat the knitting process as something as delicate as lace making, others experiment with materials unheard of (fur, metal, rope), it is very exciting to watch these new talents.

Kevin Kramp A/W 2009-2010 (c) 2009 ACM Photography + Kevin Kramp

What do you think of the emergence of subversive knitting and yarn-bombing?

I really like it and think it is a very positive kind of urban ‘graffiti’ and shared engagement with the urban environment. We also had a small guerrilla action here around the museum as well with knitters from Brussels who ‘protest’ against ugly buildings or city furniture by covering them in knitted plastic wraps (waste instead of a more noble material like wool). We got a lot of response to the call and it was really great to see the more routined artists from Brussels working together with the Antwerp volunteers. The police came by and said they thought it was ugly, but that was ok for the knitters, as they were actually showing the ugliness of some city sights by covering them in knitwear. It was not a very subversive or artistic act but a very fun process; what struck me is that knitting is really a social activity these days, more so than sewing, pattern cutting or other fashionable hobbies, it is something that can be done whilst talking and seeing your friends.

******* Bernard Willhelm's Spring/Summer 2004 Presentation (courtesy of Karen Van Godtsenhoven)

Bernard Willhelm SS 2004 from Sarah Scaturro on Vimeo.

" Army, Navy, Air Force, Marines," 1993, fabric, wire, vinyl, silkscreen, zipper.

" Army, Navy, Air Force, Marines," 1993, fabric, wire, vinyl, silkscreen, zipper.